The following is an essay I wrote last semester for English 3398: Writing for English Majors

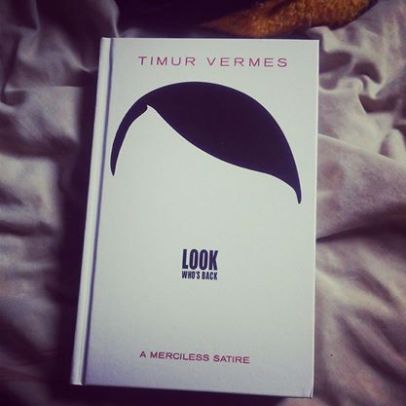

A coincidence occurred at the beginning of the semester that has left me obsessing over a particular philosophy applied to the various writing practices and prose of F. Scott Fitzgerald. A new novel by my favorite contemporary author had arrived from England on the first day of classes, and yet obligations to assigned reading would cause deviation from visions of instant gratification. It was wrongly assumed that college level students studying English would have read The Great Gatsby by this point in their academic careers. My first reading of Gatsby was a rushed and hasty experience that pleasantly aided me in avoiding my professor’s ruining of the novel at our second class meeting, when he spoiled the fact that the character for which the novel was titled dies! While there would be plenty of time for rereading the material for the purpose of deeper analysis the semester was fresh and the workload had not yet kicked into full gear. If I could get through Gatsby in a day I could surely consume a quick four hundred pages over the following weekend. In John Niven’s most recent novel Straight White Male, the main character is himself an author by the name of Kennedy Marr, who happened to speak of Fitzgerald’s name no less than three times. It is the final mentioning of the book in which Marr observed in passing, “what Fitzgerald called the price of admission,” (Niven, 328).

Throughout the entirety of his literary career Fitzgerald sought a greater grail than that of Gatsby’s imagination, for such dreams were part of the process. The practice of crafting a level of prose that made a piece of writing not only sellable but a work of art was the professional attitude and philosophy that drove Fitzgerald’s creative ambitions. When looking into this price of admission I came to find it referenced on a singular occasion in Bruccoli’s A Life in Letters. The context related to the craft of writing on the standards of a professional level and was directed to a friend of the family who had submitted her manuscript to Fitzgerald in seeking his advice. His reaction was less than comforting as he was honest and informed Ms. Turnbull, “I’m afraid the price for doing professional work is a good deal higher than you are prepared to pay at present. You’ve got to sell your heart, your strongest reactions, not the little minor things that only touch you lightly,” (Bruccoli, 368). He writes of these minor things as practices of an amateur as he continues, “you have not yet developed the tricks of interesting people on paper, when you have none of the technique which it takes time to learn. When, in short, you have only your emotions to sell, (Bruccoli, 368). Fitzgerald goes on to tell Turnbull about investing in the weight of specific experiences in confessing, “In ‘This Side of Paradise’ I wrote about a love affair that was still bleeding as fresh as the skin wound on a haemophile,” (Bruccoli, 368). The truth behind criticism can be excruciating when it acknowledges the failures of strategy, and the lack of anything published by a Frances Turnbull suggests the submission of defeat.

A little more than nineteen years prior to the letter to Ms. Turnbull, Fitzgerald wrote a letter to his editor concerning the first draft of a manuscript that would go on to be This Side of Paradise. Such confidence was revealed in this short letter as Fitzgerald made abstract inquires of possible publication dates in spite of the fact that Mr. Perkins hadn’t, “even seen the book,” (Bruccoli, 28). Even considering the good nature of the working relationship between Fitzgerald and Perkins the gesture of such inquiries seems intrusive and unwarranted, yet it was the confidence in his craft that merited Fitzgerald’s motivations for doing so. Such confidence is never omitted from the inconsistency of man, as Fitzgerald quickly turned around and wrote his second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned, and broke with the routine of regularly crafting prose. In between the drafts and publication Fitzgerald took a break from his work to indulge in the leisure of the free time afforded him. In a letter to Perkins, Fitzgerald explained the psychological consequences of an ambitious man in the midst of a period of sloth, “because I’ve loafed for 5 months + I want to get to work,” (Bruccoli, 48). Not keeping up with any regular practice will damage one’s craft, and for Fitzgerald not keeping up with the craft put him, “in this particularly obnoxious and abominable gloom,” (Bruccoli, 48). The shortcoming of his gloom resulted in the deteriorating of his confidence as he wrote, “I haven’t the energy to use ink-ink the ineffable destroyer of thought, that fades an emotion into that slatternly thing, a written down mental excretion. What ill-spelled rot!” (Bruccoli, 48). This confession reveals the profoundness of Fitzgerald’s obsession and dedication to the craft in the reflections of momentary failure. In spite of his first two novels the philosophy of the price was in a state of development to this point.

From failure to the grindstone, Fitzgerald progressed in his approach to Gatsby. One lesson I’ve learned as a developing writer is to never be married to the manuscript as is. Writing is rewriting, and such is included in this price of admission. Through the revisions of editing Fitzgerald admits that regardless of how much time the process may consume, “I cannot let it go out unless it has the very best I’m capable of,” (Bruccoli, 65). For the sake of getting work done I’ve become acquainted with the mantra of, ‘don’t get it right, get it writ,’ and maybe that’s relevant for the vigorous constructing of a first draft. But Fitzgerald’s longevity can be contributed to his taking the time to get it right in spite of deadlines. If he were to have pushed the work and conformed to the commercial styling of authors that pump out a novel every year Fitzgerald may have considered himself, “dead with those who think they can trick the world with the hurried and the second rate,” (Bruccoli, 183).

Second rate was not of Fitzgerald’s fashion as he revealed the formula in his letter to Ms. Turnbull, “You’ve got to sell your heart, your strongest reactions,” (Bruccoli, 368). On selling his heart to Gatsby, Fitzgerald described in a letter to Zelda how difficult it actually was to apply the developing philosophy, “I thought then that things came easily- I forgot how I’d dragged the great Gatsby out of the pit of my stomach in a time of misery,” (Bruccoli, 187). Focusing on negative memories in a time of misery seemingly creates a vicious cycle, but Fitzgerald included his strongest reaction to the bitterness of a previous romance in the form of Tom Buchanan’s polo ponies as the woman he coveted, “married a man with a string of polo ponies. Fitzgerald never forgot Ginevra King-he saved all her letters-and Jay Gatsby’s timeless love for Daisy Fay, who also married a man with a string of polo ponies, undoubtedly had its roots in his memory of her,” (Miller, 5). This example of a simple truth from Fitzgerald’s life seems transparent at first glance, but it’s inclusion in The Great Gatsby reveals the selling of Fitzgerald’s own heart.

Following Gatsby Fitzgerald strove to outdo his previous effort, “Gatsby was far from perfect in many ways but all in all it contains such prose as has never been written in America before. From that I take heart. From that I take heart and hope that some day I can combine the verve Paradise, the unity of the Beautiful + Damned and the lyric quality of Gatsby, its aesthetic soundness, into something worthy of the admiration of those few,” (Bruccoli, 112). Fitzgerald’s confidence contained parallels with Gatsby’s dream in that it was all about the chase and the moment. Once obtained, it is fleeting and holding onto the moment is impossible. Fitzgerald’s personal satisfaction with his work was a fleeting sensation, and it was only the prospect of outdoing himself that he remained wholly dedicated to chasing a dreamlike vision that he could never quite grasp. “That, anyhow, is the price of admission,” (Bruccoli, 369).

Doctor David Gershom Myers

Doctor David Gershom Myers