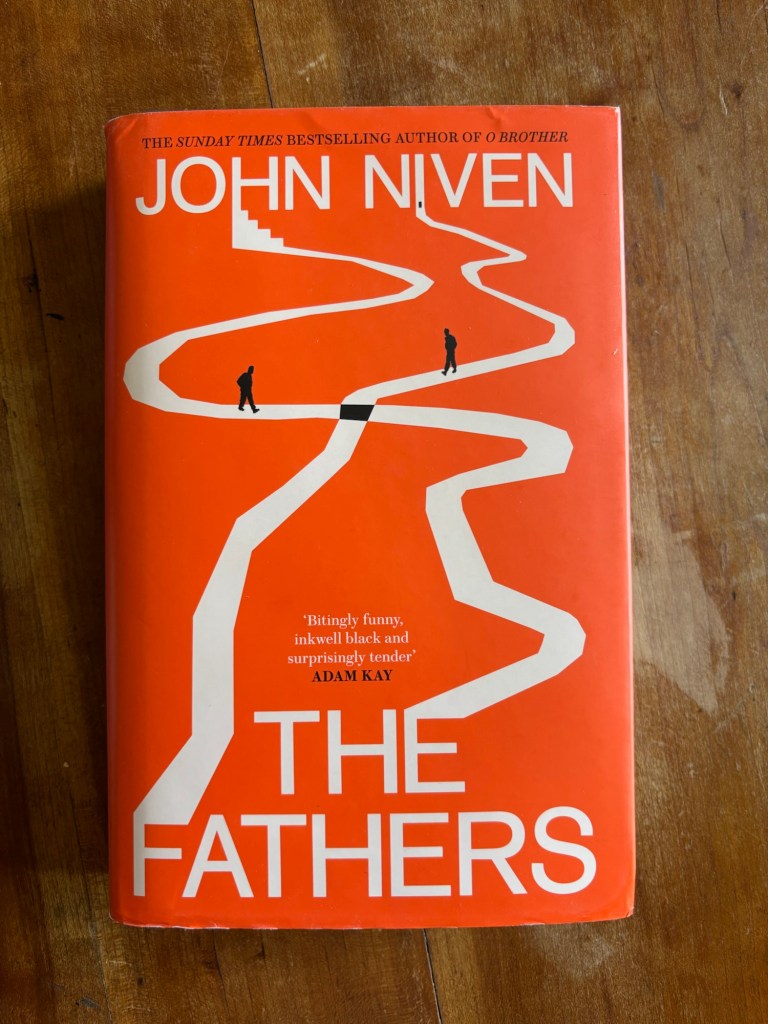

A coincidence is all that’s necessary to set into motion matters of fortune and fate. What joys and tragedies are stirred as a consequence of experience? Two families each welcome their own baby boy, both born on the same day…and while meandering around the hospital, their fathers meet by chance. Friendships form, but not here…Dan and Jada couldn’t be more different, but when Dan’s world collapses, Jada becomes something of an enabler, and from there things spiral out of control in a pure ‘John Niven fashion’ that dropped my jaw more than thrice. ‘The Fathers’ is a top shelf addition to Niven’s body of work.

This book had me laughing out loud multiple times, tear up on a few occasions, and with one moment I set the book to the floor and wept. I hadn’t been hit this hard since ‘The Blood of the Lamb’ by Peter de Vris. It’s a strange and liberating thing when art elicits an emotion you weren’t anticipating. I expect Niven will get me to laugh, think, and potentially cause me to shed a tear or two, but this was full-blown uncontrollable quiet weeping in the night. John is the kind of writer who conveys the human experience with such grace and grit, his work is nothing but the highest quality, and ‘The Fathers’ is his finest piece of fiction yet.

My only criticism is that it had to end. This was such a pleasing read. From the heights to the lows beneath whatever you’d call ‘rock bottom’ of parenting, to a world of crime that ranges from petty to ultra violent, to the critique and commentary on class pitfalls and privileges, ‘The Fathers’ contains a range that keeps pages turning. The tone pivots from sentimental to wretched as quickly as one could read, and those moments are laid out in such a way…never thought I’d find myself laughing so hard at the description of a McDonald’s apple pie.

To break my heart with fiction is possible, but this book destroyed me. The obsessive ‘what-if’ moments that followed the tragedy is something that will trouble those knee-deep in grief.

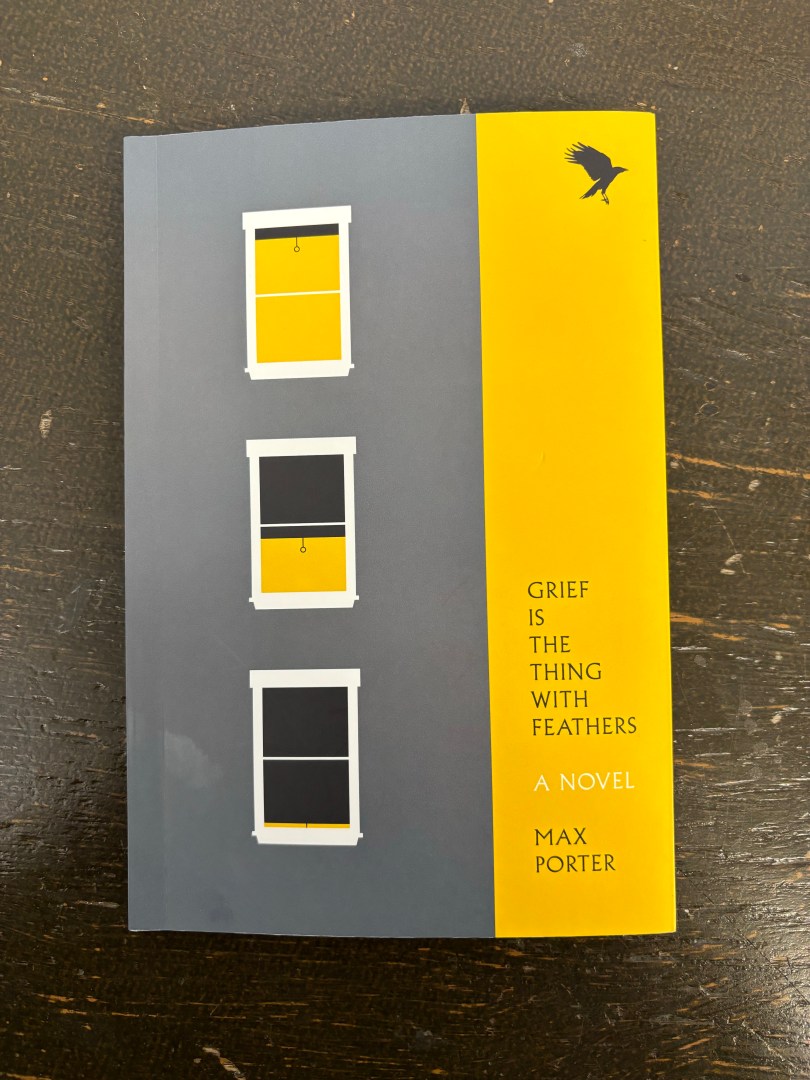

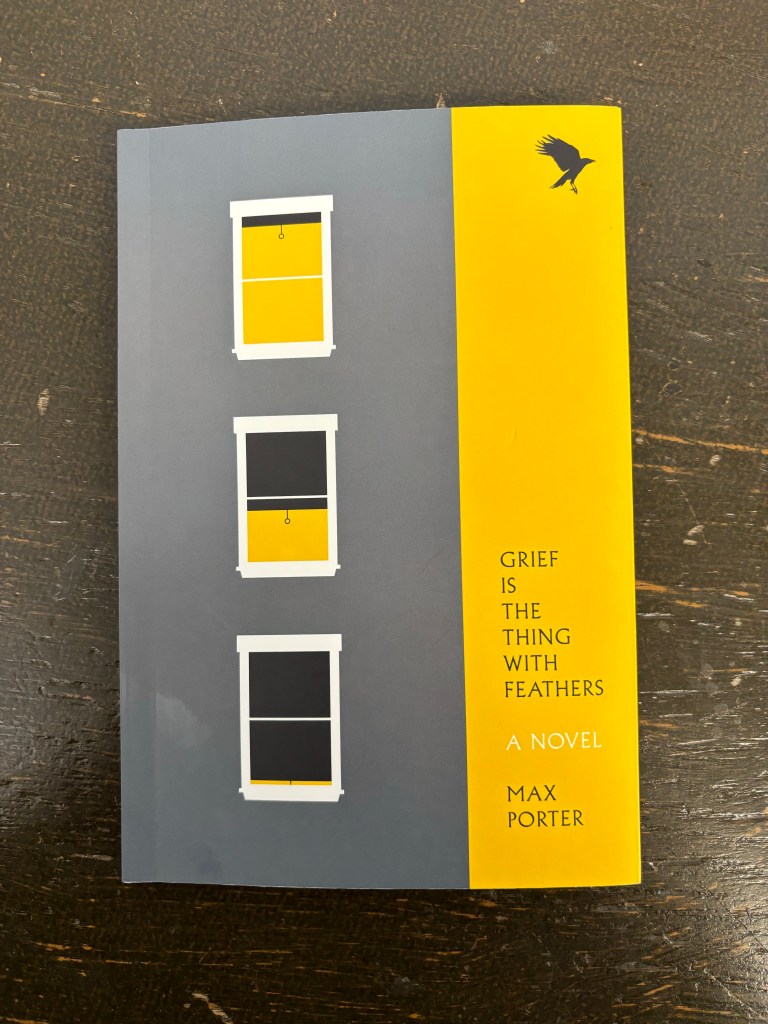

In another book that broke my heart, ‘Grief is the Thing with Feathers,’ a crow describes grief as an essential part of life, but to beware one’s dealings with grief do not dissolve into despair. Dan went beyond despair…finding a tunnel beneath his own rock bottom, and his character development surprised me. His mindset is as captivating as it is tragic. I thoroughly enjoyed ‘The Fathers’ by John Niven. I needed every bit of this book.